Processing Content

- Key insight: The banking industry has underestimated how much structure AI requires to be useful at scale.

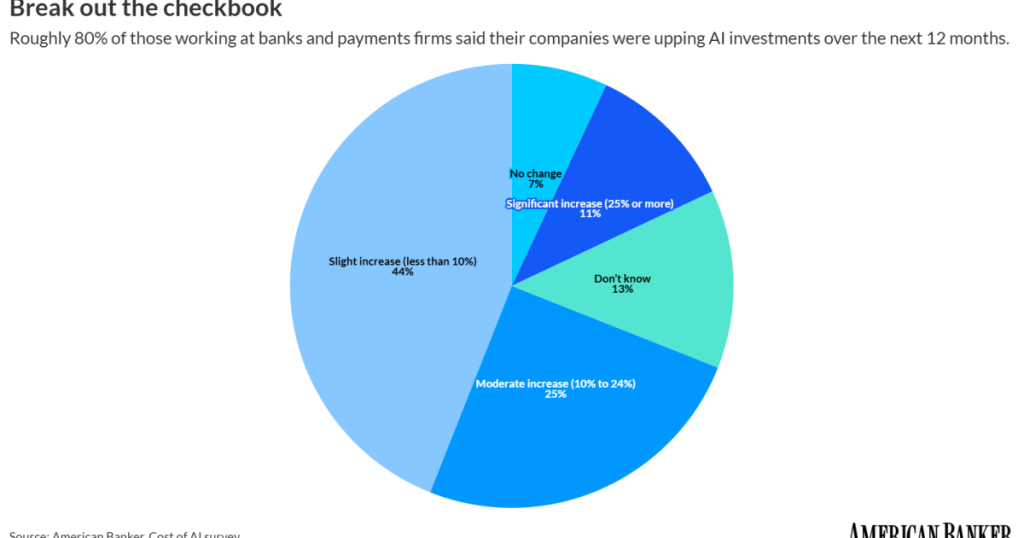

- Supporting data: Eighty percent of U.S. banks are planning to increase their AI spending.

- Forward look: Until perspectives and expectations change, the most powerful AI technology will fall short.

Leaked Bank of America emails reveal employees

But Bank of America’s experience isn’t evidence that enterprise AI doesn’t work. Banks are

One of the biggest failings I see is

AI isn’t like traditional software. Two analysts can use the same model, with the same data access, and arrive at different outcomes. Not because one is wrong and the other is right, but because experience dictates how narrowly the question is framed, what assumptions are embedded in the prompt, and how the output is interpreted.

Training, like Citi’s rollout to

You can teach employees how to write better prompts, but you can’t train away subjectivity, and each bank and lender will have different policies. Institutional knowledge that AI won’t know unless it’s baked in. When outputs depend heavily on individual skill, you don’t get scalable productivity, you get analyst-to-analyst variance.

This inconsistency gets compounded by how individuals respond to the technology itself. Some employees see AI as amplifying their capabilities while others view it as threatening their expertise or adding complexity without clear benefit. When adoption is optional or implementation is unclear, the skeptics often shape the narrative, and promising pilots stall out before they reach meaningful scale.

What’s going wrong is that banks are deploying extremely powerful systems but expecting generalist employees to operate them safely and consistently without redesigning workflows around the technology. The result is impressive demonstrations, followed by hesitation, uneven adoption and internal concern about reliability.

The real risk isn’t that AI produces bad answers. It’s that it produces answers that look reasonable, but are arrived at through undocumented logic, inconsistent prompts and ad-hoc usage. If two analysts reach different conclusions using the same AI system, which one is correct? Which assumptions are approved? Which process is defensible?

These aren’t hypothetical concerns. They’re exactly the questions regulators will ask as AI becomes embedded in credit decisions, risk assessments and investment analysis.

Seen through that lens, Bank of America’s struggle isn’t unique. Most banks experimenting with enterprise AI run into the same friction.

The solution isn’t more training or better prompts. It’s a reframing of responsibility. In banking, AI shouldn’t behave like a blank canvas. It should be constrained, productized and embedded into workflows in ways that minimize individual interpretation. The system should adapt to banking’s requirements for consistency and explainability, not the other way around.

That means fewer general-purpose tools and more domain-specific AI systems. More guardrails, not fewer. And a shift away from the idea that every employee needs to become an expert prompt engineer.

The lesson from Bank of America’s internal emails isn’t that AI is too complex for banking. It’s that banking has underestimated how much structure AI requires to be useful at scale. Until perspectives and expectations change, even the most powerful AI technology will fall short.

However, here’s the kicker; those that do master this now, will unlock unprecedented growth in a way others struggle to understand or match. New market leaders will emerge as major disrupters, not because AI failed to support the generalists, but because others approached AI as a fundamental change to how they work. They avoided treating it like a bolt-on and embraced the notion that people management, and how our organizations are designed, is at the heart of success for every major digital transformation.